This article originally appeared in Bitcoin Magazine’s “Moon Issue.” To get a copy, visit our store.

“What should the time preference of my magazine article be?”

It’s a question I first pose to author Saifedean Ammous as we walk a darkened city sidewalk, the only light reaching us from nearby restaurants where smiling diners idle.

Observing what could be any busy suburban food court, my initial impression of Lebanon is that it seems undisturbed, even normal, a far cry from the headlines heralding a once-in-a-century economic crisis defined by annual inflation that’s now the highest in the world at 140%.

But if busy Beirut doesn’t appear eager to play poster child for the ills of the fiat financial system, Saifedean is quick to note the streetlights out above us, a casualty of government budget cuts.

“The market,” Saifedean says, “is simply finding a way.”

It’s the start of a series of discussions to take place over days as we explore the city, consider his newly published work, “The Fiat Standard,” and probe the mysteries at the heart of Bitcoin that remain as the calendar year turns to 2022 and beyond.

Of frequent debate is what I assert is a generational divide forming between Bitcoin’s old-guard technologists and an ascendant meat-eating, family-first, Bitcoin-asa-lifestyle movement for whom Saifedean’s work has become a kind of dogma.

After all, it wasn’t long ago that Bitcoin discussion was defined by early coders who saw it solely as a software, an improving protocol for moving digital money. Today, it’s the ironclad economics of Bitcoin that dominate discourse, in no small part due to Saifedean (pronounced Safe-e-deen) and his 2018 publication, “The Bitcoin Standard.”

It’s not an exaggeration to say more people now buy bitcoin after reading the book than they do on discovering Satoshi Nakamoto’s 2008 white paper or by reviewing its code online.

So great has been the fanfare around the work, CEOs of public companies now proudly boast they’ve spent billions adopting a “bitcoin standard,” the most recent being an Australian baseball team that tweeted images of coaches teaching the book both on and off the field.

The author’s eager readers will no doubt find much to like in “The Fiat Standard,” a self-published sequel that’s arguably even more expansive in its assertion that central bank money printing is a great societal evil stretching far beyond monetary policy.

Included among its chapters are sure to be fan favorites like “Fiat Life,” “Fiat Food” and “Fiat Science” that frame state agencies like the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and issues like climate change as symptoms of government interference in freedoms, industry and family life.

Still, for his part, Saifedean pushes back on assertions he’s forging an association between Bitcoin and alternative lifestyles, or that his position and influence make him responsible for changes in sentiment among the movement.

He’s picking the bones from a coal-grilled fish, its eyes charred and blackened into its sockets, when he finally answers my more antagonistic questions directly.

“These ideas are popular because they match where Bitcoin fits in this time and place,” he says. “This is what Bitcoin is here to rescue us from, inflation and all the trappings of inflation.”

Our journey in Lebanon will offer context to the assertion.

THE FIAT SAIFEDEAN

Saifedean’s road to Bitcoin is a long one, defined by denial, acceptance and fateful encounters. It’s a meandering tale, relayed as we weave the many parked cars and traffic bollards that squeeze us often and tightly against Beirut’s straining retaining walls.

The son of a doctor, Saifedean explains he grew up in “one of those families” where you had to join the vocation or else you’re branded a failure. Still, he would be eager to break from tradition.

Saifedean, now 41, refers to these early years as the “high time preference” period of his life, the phrase (denoting a bias toward short-term decision-making) now colloquial as a critique against fiat finance thanks to its use in “The Bitcoin Standard.”

Medicine seemed like too much work, so he chose to study mechanical engineering at the American University of Beirut (AUB). We’ll spend much of our time circling this gated portion of the city, its tranquil, cedar tree gardens and soccer pitches walled off from the urban sprawl.

Once on the outskirts of the city, AUB is today besieged by quick-service restaurants and shops, its hospital serving as the center for what Saifedean calls the “COVID ritual,” and he wastes no opportunity to assert the virus is being abused to exert new forms of draconian control.

If he appears at first intent on showing me around his beloved alma mater, that interest ends when we’re beset by guards intent on making him wear a “muzzle.” “It’s a shame,” he says, scratching graying hair with an irritated hand. “It’s a beautiful campus.”

It’s another recurring theme — that for Saifedean, Lebanon is something of a cherished second home. “It was the hedonistic capital of the world,” he recalls. “If you wanted to party, enjoy yourself, have great food, great wine, there was nothing like it up until 2019.”

That’s when the current crisis began, turning “the Switzerland of the Middle East” into a country known for power outages and a diaspora that’s increasingly seeking refugee status abroad.

It’s hard to piece together an exact timeline for when the issue — namely, the decoupling of the black market exchange rate (then 27,000 Lebanese pounds to the U.S. dollar) from the central bank rate (still officially 1,500 pounds to the U.S. dollar) — began, or why what followed would so strongly counter the narrative Lebanon was a “resilient” nation, always able to borrow and refinance its debt despite domestic challenges.

The situation has since been exacerbated by COVID-19 and the 2020 Port of Beirut explosion, which have combined to shutter one in five local businesses.

Born to a family that had its land confiscated by Israel in Palestine, Saifedean sees the State and its penchant for central planning as the ultimate culprit for the crisis in Lebanon, and as we walk, he proves eloquent in identifying the many effects of government intervention.

“There’s a holdout tenant stuck there who is paying something like $7 a year for rent,” he explains, pointing at a browning building he believes is the victim of misguided rent controls. “They are waiting to get paid off. All over the city these apartments are falling apart.”

There’s a certain sadness to the narration, as it’s among these buildings where Saifedean discovered his interest in economics as an undergraduate at AUB.

Back then, his attitude was different. “I thought the world needed planning. I had that kind of statist immaturity that we need to have someone in authority to tell us what to do because the world is a scary place,” he says. “I chose to go the path of fiat.”

It’s a path that would next take him to the London School of Economics (LSE), where he’d have his first encounter with the outsider Austrian economists his work has revitalized, and finally to the Lebanese American University (LAU) in Beirut, where he’d write “The Bitcoin Standard.”

There, he says, Bitcoin saved his life.

HYPERINFLATION IS HERE

THE HEADLINE OF THE ANNAHAR NEWSPAPER, THE LEADING LEBANESE NEWSPAPER READS: “(US) Dollar Rate at the Outskirts of 30 thousand Lira!” referring to the black-market rate of the USD/LBP. The Lebanese currency has lost 95% of its value to inflation since September 2019. The Lebanese central bank still fixes the official exchange rate to 1,515 while the parallel market (the official name of the black market) exchanges at around 28,000.

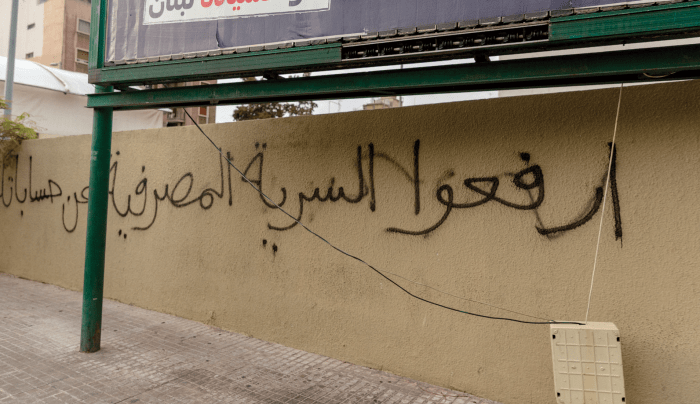

A GRAFFITI THAT READS: “Lift the bank secrecy of your accounts” on the Lebanese central bank parking wall, referring to the bank accounts of the corrupt Lebanese politicians that are accused of transferring billions of dollars to their accounts. Since October 2019, the Lebanese central bank had gradually locked access to all bank deposits for withdrawal and transfer abroad.

We’ve settled into the corner of a brightly painted café when our talk turns to Saifedean’s rising profile and how it might impair his relationships in the city. He freely admits he’s lost contacts from his former life because of his stances on COVID-19 and Bitcoin. At times, though, Saifedean seems reluctant to make the situation worse.

Despite the encouragement of our photographer Ibrahim, he isn’t initially eager to pose in front of the Banque du Liban, the central bank whose graffiti-strewn and barricaded building bears the marks of frustrations aimed at the economic downturn.

SAIFEDEAN:

It’s rubbing salt in wounds.

IBRAHIM:

You’re discussing economics.

You don’t think Salim [Sfeir, head of the Association of Banks in Lebanon] owns bitcoin?

If the offhand remark makes it seem at first as if there’s a popular awareness of Bitcoin and how it might be a solution for the crisis in Lebanon, we’ll find this isn’t exactly the case.

Saifedean puts the blame on local financial institutions that have for years pressured Bitcoin with restrictive policies. A central bank directive, he says, has been successful in turning away interest despite the fact that it’s not clear if buying and selling bitcoin is banned.

No arrests have been made, but there’s been an implied force Saifedean experienced firsthand when he would try and fail to install a Bitcoin ATM at a local shopping center in 2017. That isn’t to say others haven’t been successful.

“I know people whose banks would close their account unless you signed a paper saying you would not deal with cryptocurrencies,” he says. “They were fighting it every step of the way.”

That isn’t to say others haven’t been successful since, especially in the wake of the collapse of trust in the local banking sector.

We find a Bitcoin ATM at a nearby currency exchange, and it’s clear the operators see utility in bitcoin. They don’t want to be identified (for fear of reprisal), but they’re open about how bitcoin is allowing local Lebanese to store value safely amid trying times.

“We have thousands of dollars in our houses,” the operator explains. “They are stealing the money every time they print new notes.” You get the sense he’s wearing his wealth, his tan leather jacket looks new and it’s adorned liberally with gold chains.

The owner estimates the ATM gets about 15 customers a day, but it’s a far cry from what you might expect in a city of millions where the currency is depreciating daily.

Yet, outside the shop, life amid hyperinflation carries a certain facade of stability. Window after window on trendy Hamra Street features the latest suits and streetwear from Nike, Gucci, Rolex and the like. Under the surface, though, locals say the strain is growing.

Ibrahim is eager to explain how hyperinflation has impacted his life. He rents two houses, the result of a recent marriage. Both are similar in size and location, but he pays 1 million lira per month (or about $35) for the first, and 500 euros (about $600) for the second.

These costs are set by the contract and so don’t accomodate changes in the value of the local currency. “You can argue for both parties [of the contract],” Ibrahim says, the Canon equipment of his trade jostling in a saddlebag. “I cannot pay 500 euros. But the owner, it’s not his fault the currency devalued.”

Already, he has seen two classes of workers emerge — those who get paid by foreign firms in U.S. dollars and those who receive salaries in Lebanese pounds. For emphasis, he points to a nearby traffic guard pacing away his afternoon.

“His salary is less than $50. He used to get $800 and now he gets $50. You can imagine how this impacts his choices of food, his pleasure time,” he says.

There are losers in hyperinflation, to be sure, but there are also winners. As Saifedean explains, the situation isn’t all that bad for the wealthy. “They just got a 95% discount on their [mortgage],” he says amid dinner at a busy upscale grill.

It’s a subtle revelation that will set in over the coming days, that inflation isn’t a humanitarian crisis but a bone cancer — malignant maybe but almost undetectable on the surface.

“The people who can afford to eat here,” Ibrahim adds, “still eat here.”

BITCOIN BEGINNINGS

As Saifedean’s journey shows, it isn’t always easy to recognize economic reality — even he would spend years skeptical of the idea bitcoin was replacing gold and becoming global money.

Indeed, Saifedean’s early academic work remained steeped in the idea some authority, if only properly informed and encouraged, was capable of enacting economic and political change.

As a master’s student, Saifedean would first make a name in columns penned for Columbia’s school newspaper, The Columbia Spectator, which addressed the Palestinian struggle and the various hypocrises revealed by the Western institutions that attempted to intervene and assist it.

As highlighted by the New York Observer in 2007, Saifedean was already adept at taking an assertive stance on political issues, sparking an argument at a campus party celebrating the birth of Israel and “taking over” talk at a Hillel debate on whether Zionism is racist.

“You might as well base citizenship on the horoscope. No Scorpios are allowed, and my family are Scorpios,” Saifedean argued, the hyperbole shocking the pro- Israel lobby in attendance.

His 2011 PhD thesis, “Alternative Energy Science and Policy: Biofuels as a Case Study,” would mark the point at which he would begin channeling his antagonism toward its present targets.

Today, it reads as a prelude to “The Fiat Standard,” arguing government subsidies for biofuels actually harmed the environment. His new book revives the idea, asserting that oil and other hydrocarbon fuels should be recognized for their history of improving human life.

An attempt to unite his undergraduate engineering work with his new interest in economics, the paper found its author at first attempting to model how biofuel mandates could achieve climate goals, a direction that would sharply shift in the wake of the 2008 Great Financial Crisis.

As the global markets teetered on the edge of collapse, Saifedean began to see himself in the academics who justified bailouts for billionaires with similar spreadsheet models. That’s when, he says, he began to embrace the “Austrian perspective.”

“I figured out that people have known that the world is far too complicated, that I wasn’t alone.”

Empowered, he would keep on writing his PhD thesis, naively thinking he’d be embraced as a controversial, independent thinker. Instead, this turn toward libertarianism was met with resistance by the Columbia brass, and he remains bitter about the rebuke.

“I ignored how their entire intellectual way of approaching the world relies on their own statist, socialist central planning,” he says. That the response feels pointed is perhaps because his parents flew to New York for his graduation only to find his PhD defense had been canceled over concerns about its content. He would wait another year before receiving his doctorate.

Saifedean’s first brush with Bitcoin would occur soon after.

Arriving in New York in the summer of 2011, he had told himself he would buy 100 bitcoin for $100, but as the price quickly spiked above $30, he was turned away due to the expense and his conceited conviction that Bitcoin would almost certainly fail.

All the while, he would remain convinced gold was the answer to issues in the financial system, even attempting to found a startup to allow users to transfer the precious metal with the ease of popular digital apps like PayPal. (He would go to Switzerland to scout for physical vaults and claims to have had interest among provisional investors.)

Yet, Saifedean was then far from alone in thinking actively and thoughtfully about alternative finance, and he’d soon become more outspoken in airing his distrust in the legacy system.

Dated from late 2011 and early 2012, his initial appearances on “The Keiser Report” showcase what would become the next subject of his ongoing academic work — the idea that the United States was no longer a free market capitalist system.

Max Keiser, the show’s host, recalls trying to get Saifedean to see Bitcoin’s potential at the time but claims his attempts were rebuffed. (“He hated it,” Keiser says now.) Saifedean doesn’t remember it exactly that way but admits he remained “uninformed” on the subject until 2013. (He vaguely recalls the Keiser discussion but isn’t exactly sure it happened.)

Either way, as the price of bitcoin rose toward $1,000 that year, Saifedean began to rethink his skepticism, sending a series of emails to Keiser seeking advice on how to buy. Shortly after, he would make his first purchase and begin dating his wife in the same week.

It’s perhaps because of this personal journey that Saifedean increasingly sees his financial and domestic stability as intertwined.

“The profound heart of all of this is that it is the hardness of the money that reflects on the time preference. That is what Bitcoin allowed me to discover in myself and allowed me to put it in the book. When you have a way to store value for the future, you can provide for your future.”

“I know a lot of people who have done the same thing,” he continues, “they get into Bitcoin and get married. They started to think about the future.”

THE COVID HYSTERICS

Still, if the legacy of “The Bitcoin Standard” is the clarity with which it described the economic problems Bitcoin solves, debate remains on the extent of the societal impact of its solution.

On hand to emphasize the divide is Bitcoin Magazine’s own Aaron van Wirdum. A technology reporter in the field since 2013, his interactions with Saifedean quickly reveal how claims core to “The Fiat Standard” can feel taboo for those to whom Bitcoin is more science than politics.

Indeed, arguments quickly flare around whether removing government money from economies can have downstream impacts on healthcare, wellness and conservation, with conversation turning tense around the idea these subjects have any domain in Bitcoin at all.

Amid one discussion on how outlooks among users have clearly evolved on the matter, it’s Saifedean who uses the floor to claim Bitcoin critics all “want to eat bugs [and] wear a mask.”

Aaron calls the remark a pivot of subject, and Saifedean wastes no time in punching back.

SAIFEDEAN:

Oh yeah, you were one of the [COVID] hysterics at some point. Oh god.

AARON:

Well, it should have been tackled early and hard.

The conversation quickly escalates, with Saifedean arguing those who think like Aaron are no more than gullible cowards who have been manipulated by the Chinese Communist Party, big pharmaceutical companies and mainstream media into becoming modern fascists.

The exchange is laced with criticism against accomplices far and wide, from podcaster Peter McCormack and Microsoft founder Bill Gates (it’s not clear which exactly is part of what he calls “the manboob squad”) to Nassim Taleb (the Lebanese author who wrote the introduction to “The Bitcoin Standard” and with whom he is now engaged in a public feud).

In the span of some minutes, he’ll argue the media has been complicit in creating widespread belief in what amounts to misinformation about the virus and its transmissibility, all the while admonishing governments for using totalitarianism to fight a disease that can effectively be countered with “healthy living, nutrition, and basic hygiene.”

“There’s money in authoritarianism, there’s money to be made from surveillance, and the TV viewers go along,” Saifedean says, by now ignoring the cooling food in front of him.

As time goes by, Aaron is able to interject less and less, his final comment something along the lines of, “Do we agree that there’s a virus?” Attempts to find a middle ground only seem to make Saifedean more irate as he builds to his crescendo.

“How many years and how many shots is it going to take for you to see this isn’t about the shots or the masks? You’ve been suckered into handing over generations of freedoms that your children are never going to get back.”

“I respect your right to be gullible and stay at home. Why can you not respect my right to risk my life? It’s not about health, it’s about control. Wake the fuck up! Wake the fuck up!”

The debate is one that will reoccur over the four-day trip but never with quite the same passion. Saifedean later refers to Aaron’s insistence on “poisoning” him with the vaccine as a “disagreement among friends,” the comment offering a more muted but no less acerbic take.

If Aaron is offended by the conversation, he’s adept at hiding it. When you’ve worked through the bitter parts of Bitcoin’s formative years, getting yelled at is simply part of the trade. Still, it’s worth noting this behavior is a target for Saifedean’s critics, who worry it politicizes discussion of a neutral technology with no bearing on broader lifestyle choices.

AN UNSTABLE EQUILIBRIUM

But even as he wields it as a weapon, it’s hard not to admire the zeal with which Saifedean embraces the freedoms Bitcoin has afforded him. If you’re not the target of his animosities, he’s enjoyable company with a deep interest in food and music, and Beirut brings out his inner aficionado.

This sentimentality is understandable when you consider he’d experience a career renaissance here in 2015, when back again in Beirut, he’d publish a breakout paper that argued bitcoin was the only cryptocurrency likely to experience long-term adoption.

“The coexistence of bitcoin and government currencies is an unstable equilibrium: the longer bitcoin exists, the more likely it is to continue, and the more attractive it becomes compared to traditional currencies,” it reads.

Yet, if that work seemed tepid at times (including an obligatory passage about how innovations are often outmoded), more assertive work would soon follow. “Blockchain Technology: What Is It Good For?” and “Can Cryptocurrencies Fulfill the Functions of Money?,” bolder papers that more forcefully argued for Bitcoin as an agent of change, would appear in 2016.

But even as these works spread his message among academics, Saifedean says they did little more than encourage him to spend time “arguing on Facebook.” That’s when his wife convinced him to buckle down and write a book. Penned in two-and-a-half months thereafter, “The Bitcoin Standard” was an attempt to set the record straight, and the sales suggest it did.

For Saifedean, it’s the market reception that he finds most validating. Far from life in the fallow university system defined in “The Fiat Standard,” where paper mills compete for state handouts, he’s expanding his books into a new website, Saifedean.com, for a global customer base.

“I had to take all these incredible ideas about the world and try to write this disgusting drivel that could get past the journals nobody reads that controlled my career,” he says with no small satisfaction. “Now, I can get on the keyboard and write.”

In his mind, this is how all industries should operate, with creators giving value to consumers, not a boss who has access to the money printer. Instead, he sees his former profession (and the world at large) as full of depressed people who “don’t get to do anything of value at all.”

“You see a lot of stories of people who feel a lot of emptiness, and you don’t see that with Bitcoiners,” he continues. “[In Bitcoin], you’ve settled on this money that is the final form of money and you can save it, and you know that it’s there.”

It’s these statements that perhaps best explain how Saifedean has influenced outlooks on the future of Bitcoin itself. I argue there’s a widespread confidence now, absent from earlier times, that Bitcoin is an inevitability requiring nothing more than passive acceptance.

It’s a point we debate back and forth, with Saifedean asserting, as he has in his work, that it’s only a steady increase in value over time that will make Bitcoin more mainstream. If this sounds “unidealistic,” he’s keen to assert he’s not an evangelist, nor does he think Bitcoin needs any kind of activist outreach to accelerate its adoption.

“Hard money cannot stay niche,” he says. “If number go up, everyone is going to want in.”

ORANGE PILLING THE KING

This debate will resurface again in microcosm at a meetup later, when it becomes clear even Beirut’s Bitcoiners don’t exactly see it as a solution to the crisis. Perspectives vary, but even as conversation slips between English and Arabic, prognosis remain as dim as the pub lighting.

Wrapped in a banker’s scarf and blue blazer, Gabor sits bespectacled as he argues why the local policy institute he works for believes the best course is to establish a currency board that can encourage the central bank to back its deposits with full U.S. dollar reserves.

Soon, Saifedean is careening into our conversation from across the room, eager to play Bitcoin defender. “If it’s a committee, it’s central planning, but if you call it a board, it’s not,” he says amid protests. “If you’re not solving the problem, the money printer, you’re just jerking off.”

At the heart of the debate is Saifedean’s central thesis from “The Bitcoin Standard” — politicians that benefit from inflation have no incentive to stop it, a problem that Bitcoin, by removing government from money management, solves by design.

“Tell them to stop bitching and moaning and start buying bitcoin!” he roars.

Still, for his part, Gabor seems set on impressing the practicalities of the matter. “If they stop printing, who will pay the salaries?” he says. “If you start at this level, you have no chance of convincing them.”

Marco, a former pharmacist and the founder of the meetup group, can’t help but agree, at least out of Saifedean’s earshot. As he explains it, local Lebanese believe the crisis to be political in nature. “They say that it can be solved with a snap of a finger. There’s always an excuse,” he says. “It’s America, or Iran, or Hezbollah, whatever you want.”

Others say Lebanon has weathered similar storms before: In the 1980s, the lira inflated wildly against the U.S. dollar only to eventually stabilize. “People still believe that this is a very similar situation,” Marco continues. “They don’t see the need to use a parallel alternative market yet.”

Most believe the near-term solution is for the country to officially adopt the U.S. dollar, but not because they see any defect with bitcoin. Rather, they seem to believe it just wouldn’t gather popular support here, even if the country took the same progressive steps as El Salvador.

“We have a physics professor going live on TV, saying it twice in the same interview, that the solution for stopping the lira’s situation is shutting down the fucking internet,” Marco adds. “You tell me we can convince these people to buy bitcoin?”

A currency dealer who trades with locals over Telegram and Binance concurs, noting most of the sales he conducts are actually for the U.S. dollar stablecoin Tether. He says Lebanese want the safety of the U.S. dollar, and that to many, crypto stablecoins are the next best thing.

Gabor adds that this is how he even grows his own bitcoin position, buying USDT and selling it on an exchange when the price dips. “Most of the local Bitcoiners don’t want to sell,” he adds.

Amid the debate, the group prompts me to test the theory by conducting a trade over Telegram, so I post a message offering to sell $250 worth of bitcoin for U.S. dollars. Within a minute, I’ve received a reply from someone eager to conduct the sale.

What follows is a bizarre encounter where I shuffle into a black Mercedes only to be told by our dealer he “never touches bitcoins.” He continues to assume I want Tether, asking “ERC-20 or Tron?” until we eventually abandon the poorly translated trade.

When we return to the bar, we find the talk has taken its own unexpected turn, with Saifedean denouncing the failures of republican governments in the region. The idea will feel familiar to Saifedean readers who know his stance on monarchies as the preferred, low time preference form of state rule. But even in a bar where everyone is eager for a copy of “The Fiat Standard,” his vision for a more peaceful Middle East perhaps comes off as more polarizing than intended.

“Look at Jordan, they have security, infrastructure that works, and an entirely livable, civilized country. Plus, the Hashemites can get you 24-hour electricity,” he says, chiding the table.

To the amazement of attendees, he goes on to suggest Jordan’s ruling family might even hold the keys to resolving broader regional strife. Though they are Sunni Muslim, they are direct descendants of the prophet Muhammad, which makes them popular among Shia Muslims.

Since the entire Sunni–Shia schism, he reasons, comes from Shia anger at Sunni betrayal of the house of Hashem after the prophet’s death, only the Hashemites can mend the breach, which has turned increasingly bloody and bitter in recent decades.

“But Jordan isn’t exactly a free market economy,” objects Michael, an ex-student of Saifedean.

“We just need to orange pill His Majesty so he shuts down the parliament and ministries and all the central planners, leaving only the army and the royal court!” he exclaims, adding: “The rest of the region will want to join the Hashemites.”

CEDARS OF THE GODS

Back in the car, days of discussion appear to have finally piqued Ibrahim’s interest in Bitcoin.

We’re on our way to the Shrine of Our Lady of Lebanon, fighting stop-and-go traffic en route to the nearby national monument when his questions begin to pour forth. Should he do anything with the “other cryptocurrencies?” What does it mean when we say “China banned Bitcoin”?

He’s been busy Googling since we met, and while he was formerly impressed by a speech Saifedean gave in May, he’s on the sidelines with no money invested in bitcoin.

Ibrahim’s admission is made all the more surprising when he relays that most of his money is stuck in his bank account, all but inaccessible due to withdrawal limits.

It’s something Saifedean just can’t seem to understand. On leaving university life in 2019, he’d immediately convert his severance pay into bitcoin. (He even sent his sister-in-law to the bank directly with his dealer, so as not to waste any time.) Factoring capital controls, he’d take a 40% cut on the payment, but says the gains in bitcoin have made up for it.

“It’s like [the GIF of] George Clooney when he’s walking away from the explosion,” he recalls. “It hit 3,000 [liras to the dollar], then the numbers tumbled one after another.”

Later, we’re passing the largest Christmas tree in Lebanon as the conversation resumes.

Aaron is still probing Saif about his feelings on Big Oil, attempting to get him to admit there’s such a thing as “negative externalities” that humans need governments to help solve.

SAIFEDEAN:

They exist in situations where property rights are not well defined.

AARON:

Right, but who owns the ozone layer?

IBRAHIM:

(quietly) What is fiat?

The question is so innocent it almost doesn’t register, and I take the bullet as Saif and Aaron turn back, lost in a battle of egos running deep. The list of talking points that follows feels like a greatest hits of Saifedean’s work — the mobility problem with gold, how and why paper notes replaced it, and why bitcoin is now the best way to move value across time and space.

It’s a testament to his influence, but also to the difficulty of ever really explaining Bitcoin fully. The deeper you go, the more questions always seem to remain.

IBRAHIM:

My cousin told me recently there was a security upgrade… who does that?

RIZZO:

[Turning back] Yeah Saif, who does that?

SAIFEDEAN:

If you’re running the code, you decide what code you want. You can decide anything, but the thing only works if you don’t change anything.

AARON:

But it did change…

The conversation feels worn now, so much so that as potholes rattle the car, the stream of Arabic cursing that follows seems almost like a therapeutic break.

In the shock to the senses that follows, I can’t help but wonder about our time preference, if we’ve lapsed too far into our own complacency, too sure some climax was bound to happen.

In solidarity with the sentiment, I decide to override my own central planning, asking Saifedean how he’d like to end the article. “Hookers, cocaine, gunfight? You want to watch drug dealers fight in Bakka?” he responds.

Fate intervenes when, just down the street from our destination, he asks me abruptly, “Oh, so did you sell your bitcoin yesterday?”

I turn back and tell the tale. The shock is visible on Saif’s face, his eyes wide, mouth ajar.

SAIFEDEAN:

That’s a sad way to end the story.

We’re at our destination now, abruptly swapping handshakes.

It’s an empty feeling as the car rolls along. As if after so many manic sword swings, the great bull had finally bled, and we were left sitting with some great and sobering wrong.

NO SAD ENDINGS

It’s not soon after that we’re again at the hotel, and I’m lost looking at waves lapping into mist as Ibrahim turns to the subject of payment.

I’m out of dollars by now but figure an ATM might be near. If nothing else, it could be the set up for another ending, another caper, a final quest that could tie the ragged ends of a trip that has seemed to end abruptly, the false note struck in the car still ringing.

I almost don’t hear the words as he finally breaks the silence.

“I will do it,” Ibrahim says, half as if he’s still convincing himself. The words are quick, hushed, paired with a kind of stowaway smile.

Some minutes later he’s marveling as bits fly through cyberspace, and Bitcoin, that great central bank in the sky, reassigns our private keys, the soft magic making what was mine his, for all time, forever, or as long as we can hold it.

It’s a tiny rebellion against the fiat world, to be sure.

Out there in the night, there remain the big banks, self-important soldiers, and all the tentacles of the expanding, encroaching global state. But it’s these moments where it’s clear it might be our aspirations more than our answers that really matter most.

“Wow,” Ibrahim says, looking down at the soft glow of his phone.

You can see it for a second — the reflection on all the ATMs, the broke central banks, the arguments over ripped bills — the understanding that it could all be so easily wiped away.

Source: https://bitcoinmagazine.com/culture/life-after-the-death-of-fiat