The search for Satoshi Nakamoto, Bitcoin’s mysterious inventor, has been an ongoing hunt for the last 13 years. Since 2014, dozens of so-called candidates have appeared, but none of them have convinced the greater community that they are Bitcoin’s creator. Furthermore, journalists from publications like Newsweek have pointed to a few specific individuals, and nearly every one of them has denied playing a role in the creation of the world’s leading crypto asset. In October 2011, a journalist thought he discovered Nakamoto’s identity, or felt like he offered enough compelling evidence about his discovery to suggest the person he found may have created the first digital currency.

Putting the Wrong Face on the Person Behind Bitcoin

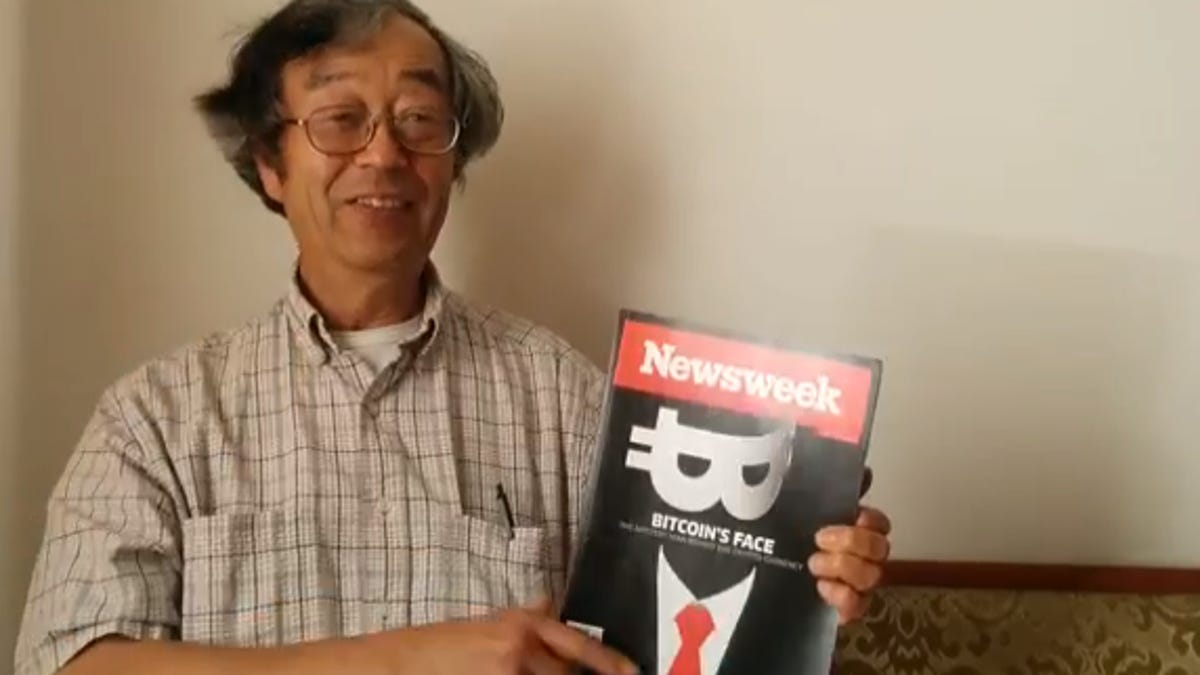

Over eight years ago, Newsweek journalist Leah McGrath Goodman published a story called “The Face Behind Bitcoin,” and in the article, she claims Satoshi Nakamoto was a retired physicist named Dorian Nakamoto. Despite Dorian’s denial from the beginning, the Newsweek reporter published an exposé about Dorian’s life. She claimed that there were several similarities between Dorian and Bitcoin’s anonymous inventor.

Dorian Nakamoto holding the Newsweek article. Dorian has denied he is Satoshi Nakamoto and noted that he misunderstood the Newsweek reporter Leah McGrath Goodman.

Dorian Nakamoto holding the Newsweek article. Dorian has denied he is Satoshi Nakamoto and noted that he misunderstood the Newsweek reporter Leah McGrath Goodman.

Dorian wasn’t happy with the exposé and he told the public he felt victimized and highlighted that he misunderstood Goodman’s questions. Bitcoiners were not too pleased with Goodman’s Newsweek story, and the community backed Dorian’s victim commentary by noting the Newsweek journalist doxxed Dorian by showing a photograph of his home in California. Goodman received a great deal of backlash for her story, but she wasn’t the only journalist who tried to pin Nakamoto’s identity on a specific individual.

‘I’m Not Satoshi — But Even if I Was I Wouldn’t Tell You’

Roughly two and a half years before Goodman’s exposé on Dorian Nakamoto, a journalist from the New Yorker tried to do the same thing. On October 3, 2011, when bitcoin (BTC) was trading for $5.03 per unit, the New Yorker’s Joshua Davis claimed to have discovered the mysterious inventor, and his name was Michael Clear.

Michael Clear, the Irish computer science student, denied he was Satoshi but the New Yorker’s reporter decided to publish the story anyway. In 2013, Clear wrote a blog post begging people to stop emailing him asking about bitcoin and possible ties to Satoshi Nakamoto. “I was naturally startled when he thought I could be Satoshi, and there was some humor and regrettable mistakes on my part,” Clear said at the time. However, various misinterpretations and losses of context along with some misleading summaries in further reports, unfortunately, helped trigger the whole thing.”

Michael Clear, the Irish computer science student, denied he was Satoshi but the New Yorker’s reporter decided to publish the story anyway. In 2013, Clear wrote a blog post begging people to stop emailing him asking about bitcoin and possible ties to Satoshi Nakamoto. “I was naturally startled when he thought I could be Satoshi, and there was some humor and regrettable mistakes on my part,” Clear said at the time. However, various misinterpretations and losses of context along with some misleading summaries in further reports, unfortunately, helped trigger the whole thing.”

Davis was first clued in on Clear when he attended the Crypto 2011 conference and started to highlight attendees that either lived in the U.K. or Ireland. Six of the cryptographers he highlighted all attended the University of Bristol, but when he asked about their involvement with bitcoin one of the cryptographers said:

It’s not at all interesting to us.

Davis noted that Clear was a cryptography graduate student from Trinity College in Dublin. Clear was awarded the top computer-science undergraduate award at the college in 2008. Following the award, Clear went to work for Allied Irish Banks and published a paper on peer-to-peer (P2P) technology, and Davis noted that the paper was written with a British writing style.

In 2011, Clear met with Davis during the reporter’s investigation, and he told the journalist he liked to keep a low profile. Davis said the 23-year-old told him he had been programming since he was ten, and the cryptographer was very proficient in C++ as well. Davis stressed in his editorial that Clear was responsive and calm when he was asked about bitcoin.

“My area of focus right now is fully homomorphic encryption,” Clear told Davis. “I haven’t been following bitcoin lately.” Clear also told Davis that he would review the Bitcoin codebase and in a later email, Clear insisted that he could “identify Satoshi.” Clear also said he believed it would be unfair to doxx Nakamoto after all the steps the inventor took to remain anonymous.

“But you may wish to talk to a certain individual who matches the profile of the author on many levels,” Clear said. The person Clear mentioned was a man named Vili Lehdonvirta, and he immediately denied being involved with inventing Bitcoin. Davis then got back in touch with Clear and told him “Lehdonvirta had made a convincing denial.”

The New Yorker’s author then asked Clear again whether he was Satoshi Nakamoto. “I’m not Satoshi,” Clear responded. “But even if I was I wouldn’t tell you.” Clear also added that taking bitcoin down would be extremely hard. “You can’t kill it,” Clear insisted. “Bitcoin would survive a nuclear attack.”

Three Men and the Encryption Keys Patent Created 72 Hours Before Bitcoin.org Was Registered

Despite the denial, Davis and the New Yorker decided to publish the piece about Michael Clear, and the story was picked up by a number of media outlets that year. Clear once again insisted that he was not Nakamoto, when he spoke to reporters from the publication irishcentral.com.

“My sense of humor when I said ‘even if I was I wouldn’t tell you’ is missing, this was said jokingly,” Clear explained. “[I] found it funny that The New Yorker reporter thought I was Satoshi, but I have always (beyond conversational jokes like the quote above) vehemently denied it. I could never allow myself to be even remotely given credit for someone else’s creativity and hard work.”

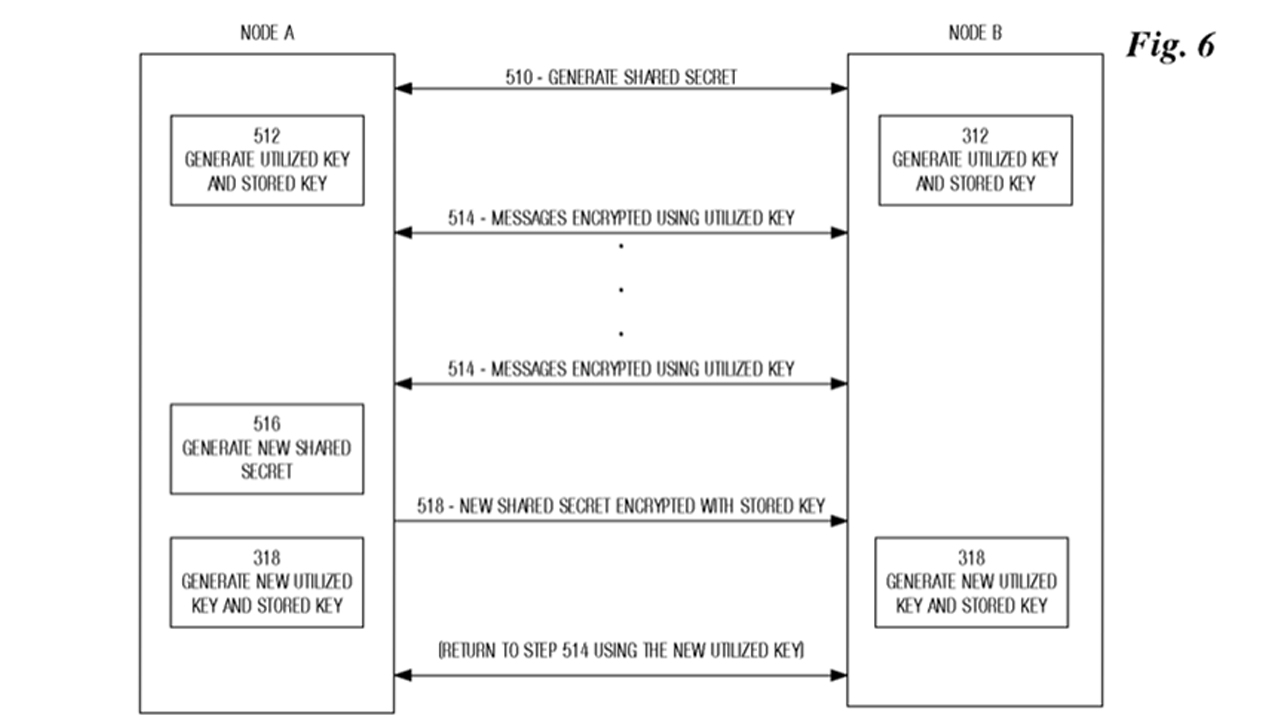

The United States patent #20100042841A1 authored by Neal King, Vladimir Oksman, and Charles Bry.

The United States patent #20100042841A1 authored by Neal King, Vladimir Oksman, and Charles Bry.

The New Yorker’s article was one of the first times a journalist had tried to pin someone’s identity to the creation of Bitcoin, but it would not be the last. Just one week later, the publication Fast Company and the reporter Adam L. Penenberg published another Nakamoto story with a mysterious angle.

Penenberg believed his evidence was more compelling, and he identified a patent that was created three days before bitcoin.org was registered called “Updating and Distributing Encryption Keys.” This was enough evidence for Penenberg to question the creators of the patent: Neal King, Vladimir Oksman, and Charles Bry.

Similar to the New Yorker exposé, all three of the suspected individuals denied they had any involvement with creating Bitcoin. Penenberg concluded that the point of his editorial was not to claim Fast Company found Nakamoto, but to “show how circumstantial evidence, which is what the New Yorker based its conclusions on, isn’t synonymous with truth.”

Despite the fact that both of these editorials led to dead ends and rabbit holes leading nowhere, journalists hunting for Nakamoto have tried with great effort to expose Bitcoin’s inventor and tell the world who this remarkable individual really was. So far, none of the Satoshi Nakamoto exposés have revealed anything that even offers a closer look at Bitcoin’s inventor — just speculation and coincidences that have very little meaning.

Tags in this story

Adam L. Penenberg, Bitcoin, Bitcoin’s Creator, Bitcoin’s Inventor, BTC, Charles Bry, Dorian, dorian nakamoto, Fast Company, Joshua Davis, Journalists, Leah McGrath Goodman, media reports, Michael Clear, Nakamoto, Neal King, New Yorker, New Yorker’s Joshua Davis, Newsweek, Satoshi Nakamoto, Satoshi Nakamoto exposés, Vili Lehdonvirta, Vladimir Oksman

What do you think about the first Satoshi Nakamoto exposé published by the New Yorker in October 2011? Let us know what you think about this subject in the comments section below.

![]()

Jamie Redman

Image Credits: Shutterstock, Pixabay, Wiki Commons, United States patent #20100042841A1, Reddit,

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only. It is not a direct offer or solicitation of an offer to buy or sell, or a recommendation or endorsement of any products, services, or companies. Bitcoin.com does not provide investment, tax, legal, or accounting advice. Neither the company nor the author is responsible, directly or indirectly, for any damage or loss caused or alleged to be caused by or in connection with the use of or reliance on any content, goods or services mentioned in this article.