This article originally appeared in Bitcoin Magazine’s “Censorship Resistant Issue.” To get a copy, visit our store.

Look Ma, No Hands

I’ve wanted to be a doctor for as long as I can remember.

When I was seven years old, my father bought me a bicycle for my birthday. He wheeled it into the living room with childlike enthusiasm, sure that he was about to score a ton of dad points.

The bike was immaculate. It had all the bells and whistles a kid could dream of; it was the kind of thing that would make any kid in the neighborhood jealous.

I took a long look at my father, now knelt in front of me with a smile tattooed on his face, then at the bike and finally back at my father again.

I mustered up a sigh and shook my head.

“I can’t ride this bike. I want to be a doctor. I don’t want to ruin my hands.”

My mother loves to tell that story. Quite frankly, I don’t mind hearing it from time to time. Aside from being a vivid reminder of my childhood ambitions and providing evergreen entertainment, it is one of the last memories I have of my father. He died soon after, at a tragically young age, from a heart attack caused by an undiagnosed, treatable medical condition.

This tragedy severely impacted my formative years. My childhood and adolescence were marred with a continuous stream of trauma, tragedy and grief, punctuated by brief moments of respite. Unsurprisingly, it took quite a toll on me. As a result, I found myself on a path of nihilism and self-destruction. I was aimless, hopeless and helpless.

My future was bleak.

And then, I caught a break.

To The Moon

To escape the harsh realities of the outside world, I spent an inordinate amount of time in the school library. I read everything I could get my hands on, from Twain to Tolkien to Dostoevsky. It wasn’t long before I stumbled upon the ancient philosophers. I was captivated by the timeless nature of the human condition and the shared experiences of people across time and space. The wise words of Plato, Aristotle and Aurelius became invaluable tools in my self-development in adolescence and early adulthood.

Over an extended period of time, and not without significant setbacks along the way, I finally found myself in a relatively favorable position in life. That is to say, I was not fully immersed in survival mode during most of my waking hours.

For the first time in my life, I could realistically set my sights on a goal.

I aimed at the highest target I could think of; my childhood dream of becoming a medical doctor.

It was my moonshot.

A Hard Pill To Swallow

The career of a medical doctor, and the path to becoming one, is a rather unique human experience that can not be adequately articulated to an outsider. However, that won’t stop me from trying.

First and foremost, it can be more accurately described as a vocation — like priesthood — rather than a typical job or career. Meticulously planned life choices are made from a very young age to set the professional wheels in motion for a lifelong commitment to the craft.

There are a seemingly endless set of hoops to jump through. Excellent academic marks and SAT scores are required in high school to compete for limited positions at an elite university. Likewise, excellent academic marks and MCAT scores are required in university to compete for limited positions at an elite medical school. Once more, excellent academic marks and strong letters of recommendation are required in medical school to compete for limited positions in a residency program. Waiting for you on the other end of that brutal undertaking is an even more grueling one with residency, licensing exams and board certifications. Any time not spent in the classroom, hospital or buried in textbooks, is dedicated to working additional healthcare jobs, conducting academic research or participating in extracurricular activities to bolster the résumé and outcompete other prospective candidates for the limited spaces on every rung of the professional ladder.

The relentless pressure to perform and the immense responsibility of having other peoples’ lives in your hands day after day would take a physical, psychological, emotional and spiritual toll on any human being.

It is a journey that commonly spans from adolescence well into adulthood. While a person grows and develops drastically during this critical period of life, they must remain steadfastly focused on a rigid career path to arrive at the desired destination. Missed family gatherings and weddings of friends, fractured relationships, hundreds of thousands of dollars of debt and general life instability are the norm.

I would actively discourage a career in medicine for most prospective onlookers, with rare exceptions.

First, Do No Harm

Taking the Hippocratic Oath was one of the proudest moments of my life.

It marked the culmination of the journey of becoming a medical doctor and set a benchmark as to what is to be expected of me going forward.

Many laypeople have never read the full text of the Hippocratic Oath, and some of my colleagues seem to need a refresher, so I have included it below:

I swear by Apollo Healer, by Asclepius, by Hygieia, by Panacea, and by all the gods and goddesses, making them my witnesses, that I will carry out, according to my ability and judgment, this oath and this indenture.

To hold my teacher in this art equal to my own parents; to make him partner in my livelihood; when he is in need of money to share mine with him; to consider his family as my own brothers, and to teach them this art, if they want to learn it, without fee or indenture; to impart precept, oral instruction, and all other instruction to my own sons, the sons of my teacher, and to indentured pupils who have taken the Healer’s oath, but to nobody else.

I will use those dietary regimens which will benefit my patients according to my greatest ability and judgment, and I will do no harm or injustice to them. Neither will I administer a poison to anybody when asked to do so, nor will I suggest such a course. Similarly, I will not give to a woman a pessary to cause abortion. But I will keep pure and holy both my life and my art. I will not use the knife, not even, verily, on sufferers from stone, but I will give place to such as are craftsmen therein.

Into whatsoever houses I enter, I will enter to help the sick, and I will abstain from all intentional wrong-doing and harm, especially from abusing the bodies of man or woman, bond or free. And whatsoever I shall see or hear in the course of my profession, as well as outside my profession in my intercourse with men, if it be what should not be published abroad, I will never divulge, holding such things to be holy secrets.

Now, if I carry out this oath, and break it not, may I gain for ever reputation among all men for my life and for my art; but if I break it and forswear myself, may the opposite befall me.

-Hippocrates of Cos, The Oath (Translation by W.H.S. Jones)

I took my oath seriously.

I carried around a copy of the text with me in my wallet at all times, the way some people do with photos of their grandchildren. Over time, I had read it enough to be able to recite it at will and did so regularly as a form of meditative practice and a routine reminder of my duty to my patients.

Throughout my medical training and practice, I continued to pursue a self-motivated education outside of the classroom. Thomas Sowell and Dr. Ron Paul, in particular, captured my attention. The concepts of economic and social incentives, individual sovereignty, free speech and sound money were like water to the seeds that had been planted in the fertile mind of my youth. Ultimately, the deep exploration of these concepts made me a better doctor by bolstering my understanding of the deep-seated failures of the healthcare system I operated in and hardening my commitment to patient autonomy and informed consent.

Even so, I found myself swimming against a heavy current. The healthcare system, increasingly overrun with bureaucratic middlemen, from hospital administrators to pharmaceutical companies to insurance companies, has surgically dismantled the core of medical practice, the doctor-patient relationship.

The increased complexity of the system has made it fragile by nature. Cracks in the system have appeared before, with the opioid crisis serving as the most recent prominent example. We continue to paper over the cracks rather than address the underlying issues plaguing the system.

Kicking the can down the road, the preferred strategy of the bureaucratic decision-makers works well enough… until it doesn’t.

Two Weeks To Destroy Your Life

It was a typical weekday morning.

While scrolling through my Twitter feed and having my morning coffee, I found myself transfixed on one bizarre video after another of people suddenly collapsing in the streets of China, picked up by a group of people dressed in hazmat suits. Though much of the information coming from China at the time turned out to be misinformation or even outright propaganda, the scenes were undoubtedly startling in the moment.

It is my firm belief that the following two years in the timeline of events will be looked back upon by future generations as an egregious failure of public policy, a complete disregard for patient autonomy and informed consent, and a series of heinous human rights violations.

The crux of this text will not focus on relitigating the Science™ of masks, lockdowns, curfews, treatment options and vaccines. Instead, it will focus on the broader topics of free speech, censorship and the state of our trusted institutions, as told through my experience as an academic and medical doctor during the COVID-19 crisis.

A Perfect Storm

Charlie Munger once famously quipped, “Show me the incentives and I will show you the outcome.”

With the onset of COVID-19, all of the rot that had been festering beneath the surface for decades upon decades was suddenly exposed to the light for all to see. The perverse incentive structures, spurred on by the Cantillon effect of a fiat currency system disproportionately favoring special interest groups near the money spigot, were on full display.

On an institutional level, pharmaceutical companies were incentivized to push their products to market with speed and volume for the sake of profit; a reasonable approach for any business. In theory, they are meant to be regulated by governing bodies like the CDC and FDA, among others. In practice, these governing bodies enabled and encouraged reckless behavior by demonizing early treatment options and the repurposing of cheap, safe, readily available drugs such as Hydroxychloroquine and Ivermectin, relaxing standard safety and efficacy testing requirements for novel vaccines, and unshackling the manufacturers from the liability protection traditionally put in place to protect consumers.

Hospitals began to focus most of their attention on COVID-19, a reasonable approach. To do so, however, they reduced or eliminated significant portions of other services to accommodate the effort. The unintended consequences, which include the likes of undiagnosed cancers due to canceled screening appointments, may never fully be accounted for.

“There are no solutions, only trade-offs.”

-Thomas Sowell

Furthermore, many hospitals were incentivized, mainly through government funding, to manipulate data and overcount COVID-19 hospitalizations and deaths. This, in turn, fed the news media fear machine and affected decisions downstream from resource allocation to public policy decisions.

Academic institutions, whose research is funded in large part by government grants and special interest groups, were incentivized to toe the party line and act as a mouthpiece for the state.

Governments, as always, are incentivized to expand their dominion over its citizenry and serve the special interest groups fighting and clawing to get closer to the levers of power bestowed upon the state by the money printer.

On an individual level, employees in the healthcare system, such as doctors and academics, are incentivized to fall in line.

Consider that the average person on these career tracks spends over a decade of their lives and hundreds of thousands of dollars in student debt on their education and training, only to find themselves at the bottom of a strict hierarchy. By speaking up and causing a stir, those at the bottom of the totem pole, saddled with debt, risk losing their newly attained, highly specialized careers with few alternative career prospects on the horizon. Meanwhile, those at the top have spent decades climbing the career ladder and would be sacrificing comfortable positions, high-paying salaries and elevated status among their peers by speaking up. Silence through fear or comfort is silence nonetheless.

None of this is to suggest that all participants in the system will act according to incentives at all times. Instead, it suggests that specific actions, behaviors and attitudes will be favored on the whole, at scale, over time — the end result is a system of institutionalized corruption and cowardice.

The next layer of the onion involves the handling of those who do dare act against the system’s incentivized actions, behaviors and attitudes.

There are many prominent examples that we can point to, such as the academic and medical professionals who signed the Great Barrington Declaration, Dr. Robert Malone, and Dr. Peter McCullough, to name a few.

Many of us did not have to look that far to witness the treatment afforded to dissidents.

Where The Rubber Meets The Road

I was thrust into an uphill battle against overreaching public policy prescriptions, fighting for information transparency, patient autonomy, informed consent based on scientific rigor, logic and reasoning, and individual liberty.

The resistance to my position was fierce. Censorship against healthcare professionals comes in many forms; deplatforming, coercion, intimidation and even direct threats to careers and livelihoods.

The hospital administration handed out verbal and written warnings of all sorts. Suspensions were handed out after it was discovered that family members of hospital patients were secretly being allowed to visit their dying relatives, despite having taken the precautionary measures of testing all parties involved and abiding by strict masking rules. The cruelty of this particular policy still pains me.

Meanwhile, in the academic realm, I found myself in the eye of yet another hurricane. The Public Health department acted in an advisory capacity to the government and helped shape many critical public policy decisions, including mask mandates, lockdowns, travel restrictions and vaccine mandates. What struck me most about this experience was the complete indifference to scientific rigor and academic discourse. The department heads and government liaisons were in lockstep, and no amount of reasoning would break that bond.

As the pressure to conform began to ramp up, navigating increasingly complex situations fraught with moral hazards became challenging.

I suddenly found myself at a defining crossroads.

Doctors were being ordered to advocate for a particular medical option for all patients, regardless of age, sex, comorbidities or overall risk profile — a proposition that would have been considered absurd, antithetical to the most basic tenets of clinical practice and grounds for malpractice in any other circumstance.

As a doctor, my role is not to make decisions for my patients. It is, instead, to provide my patients with a lay of the land by communicating risks and benefits, giving them the tools to make an informed decision on their own behalf. Of course, they may choose an option that I would not choose. So long as they do so with the proper understanding of the trade-offs, I have done my due diligence. It is not my job to play God.

Once doctors were no longer permitted to communicate honestly with patients, the situation became untenable.

On the one hand, complying with the orders would allow people to keep their careers intact. On the other hand, the title of doctor would now apply in name only, as it would require a clear violation of the sacred oath.

Dereliction of my duty to my patients was not an option, so I walked away from it all.

I do not regret my actions.

Crash Landing

In one fell swoop, I lost everything: my career as a medical doctor, my position in academia, my income, my future earning potential, the respect and adoration of my colleagues, and countless relationships with friends and loved ones who vehemently disagreed with my positions.

I plunged into total chaos.

I discovered the deepest depths of personal hell a human being could encounter on this side of the Earth’s surface. I do not wish this fate upon my worst enemy.

The abrupt nature of the experience brought to mind the practice of Tibetan monks wiping clean elaborate sand mandalas to start anew from nothing, though I am reasonably certain that the monks do not do so with several hundreds of thousands of dollars in debt.

Much like in my adolescence, I found myself on the path of nihilism and self-destruction. This time around, however, the stakes were much higher, as several brushes with death’s door can attest.

In an act of desperation, I once again turned to the ancient philosophers for guidance.

The Death Of Socrates

The story of Socrates’ trial and death, as told by Plato in four dialogues (Euthyphro, Apology, Crito and Phaedo), is a tale that stands the test of time.

In 399 BC, Socrates was put on trial on charges of impiety against the pantheon of Athens and corruption of the youth of the city-state. His trial defense was unsuccessful, and he was sentenced to death by poison hemlock by a jury of his peers. Though execution was usually carried out swiftly after sentencing, Socrates found himself imprisoned for a month due to the overlap with a sacred festival in Athens, during which no executions were to be carried out. By all accounts, he had every opportunity to escape, and his followers desperately pleaded with him to do so. However, Socrates ultimately decided to stay.

I will allow Plato to tell the remainder of the story, for I cannot possibly do it justice.

“Go,” said Socrates, “and do as I say.”

Crito, when he heard this, signaled with a nod to the boy servant who was standing nearby, and the servant went in, remaining for some time, and then came out with the man who was going to administer the poison. He was carrying a cup that contained it, ground into the drink.

When Socrates saw the man, he said: “You, my good man, since you are experienced in these matters, should tell me what needs to be done.”

The man answered: “You need to drink it, that’s all. Then walk around until you feel a heaviness in your legs. Then lie down. This way, the poison will do its thing.”

“I understand,” he said, “but surely it is allowed and even proper to pray to the gods so that my transfer of dwelling from this world to that world should be fortunate. So, that is what I too am now praying for. Let it be this way.”

And, while he was saying this, he took the cup to his lips and, quite readily and cheerfully, he drank down the whole dose. Up to this point, most of us had been able to control fairly well our urge to let our tears flow; but now, when we saw him drinking the poison, and then saw him finish the drink, we could no longer hold back…

So, he made everyone else break down and cry—except for Socrates himself. And he said: “What are you all doing? I am so surprised at you. I had sent away the women mainly because I did not want them to lose control in this way. You see, I have heard that a man should come to his end in a way that calls for measured speaking. So, you must have composure, and you must endure.”

Then, he took hold of his own feet and legs, saying that when the poison reaches his heart, then he will be gone. He was beginning to get cold around the abdomen.

Then he uncovered his face, for he had covered himself up, and said— this was the last thing he uttered— “Crito, I owe the sacrifice of a rooster to Asclepius; will you pay that debt and not neglect to do so?”

“I will make it so,” said Crito, “and, tell me, is there anything else?”

When Crito asked this question, no answer came back anymore from Socrates. In a short while, he stirred. Then the man uncovered his face. His eyes were set in a dead stare. Seeing this, Crito closed his mouth and his eyes.

-Plato, Phaedo (Translation by Gregory Nagy)

Ideas Are Bulletproof

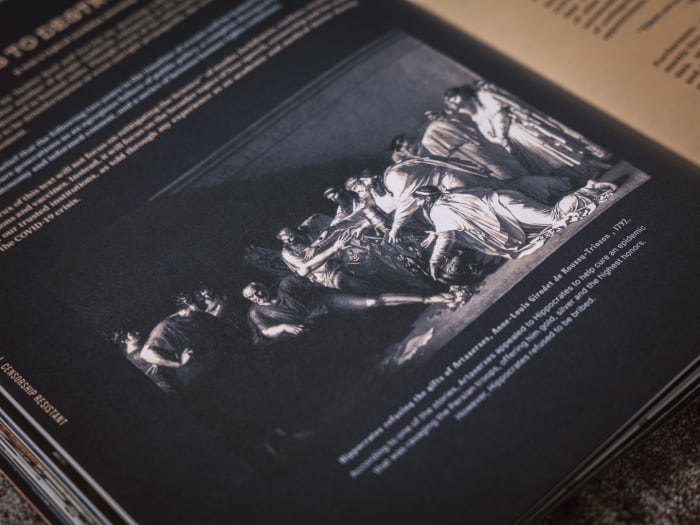

Socrates’ last words, directed at his pupil, Crito, was a request to sacrifice a rooster to the god Asclepius.

Asclepius, son of Apollo, is the god of healing and medicine. Both are referenced in the opening line of the Hippocratic Oath.

There are several interpretations as to the meaning behind this final request.

The most common interpretation posits that the sacrifice was an offering of thanks to the god of medicine for the relief from the suffering of life.

An alternative interpretation posits that the sacrifice to Asclepius, who had special healing powers, including the ability to bring the dead back to life, revolved around the resurrection of an idea rather than flesh and blood.

A conversation between Socrates and one of his followers, Phaedo, who was mourning the death of Socrates well before the drinking of the poison hemlock, gives us some insight into the alternative interpretation of the sacrifice.

Once again, from Plato’s “Phaedo”:

“Tomorrow, Phaedo, you will perhaps be cutting off these beautiful locks of yours [as a sign of mourning]?”

“Yes, Socrates,” I replied, “I guess I will.”He shot back; “No, you will not if you listen to me.”

“So, what will I do?” I said.

He replied: “Not tomorrow, but today I will cut off my own hair, and you too will cut off these locks of yours—if our argument [logos] comes to an end for us and we cannot bring it back to life again.”

What matters most to Socrates is not the death of the physical body, but the continued livelihood of the argument, or logos (which literally translates to “word”). The concept of free speech and discourse was worth dying for in his eyes.

The willingness to sacrifice everything for the sake of principles is the proof-of-work that the principles were carefully cultivated in the first place and are worth adhering to in the face of adversity.

Bitcoin Fixes This

So, where does that leave us?

I am appalled at the damage caused by reckless, myopic public policy decisions. I fear that the long-term physical, psychological, emotional and societal consequences will be impossible to properly quantify but will undoubtedly echo well into the future.

Perhaps we can find solace in the exposure of the unhinged madness of the parasite class, the continued awakening of the collective subconscious and the strengthened resolve of the remnant.

As for me, I find myself leaping wholeheartedly into the great unknown, much like Socrates.

I have experienced a painful yet illuminating career death and ego death. After much contemplation, I have come to terms with my decision.

In the end, it was Bitcoin that renewed my sense of hope and optimism.

It provided me with a safety net and allowed me to walk away from a potentially cataclysmic situation without compromising my principles.

It is my hope that a transition to a world on a Bitcoin standard will properly realign incentives and re-center the focus of medicine on the doctor-patient relationship.

Until then, I will be dedicating my life to bitcoin; a vocation that revolves around the well-being of others.

Source: https://bitcoinmagazine.com/culture/the-price-of-principles